still about Magnificent Maps, the largest BOOK in the world goes on exhibit for the first time

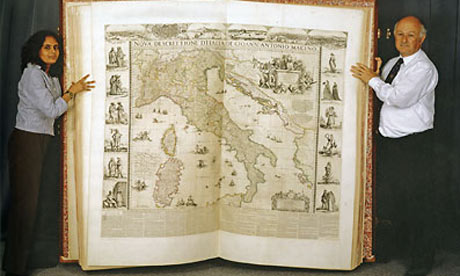

It takes six people to lift it and has been recorded as the largest book in the world, yet the splendid Klencke Atlas, presented to Charles II on his restoration and now 350 years old, has never been publicly displayed with its pages open. That glaring omission is to be rectified, it was announced by the British Library today, when it will be displayed as one of the stars of its big summer exhibition about maps.

The summer show will feature about 100 maps, considered some of the greatest in the world, with three-quarters of them going on display for the first time.

At the exhibition's core will be wall maps, many of them huge, which tell a story that is much more than geography. Many of them, said the library's head of map collections, Peter Barber: "Hold their own with great works of art."

He added: "This is the first map exhibition of its type because, normally, when you think of maps you think of geography, or measurement or accuracy."

The exhibition aims to challenge people's assumptions about maps and celebrate their magnificence, as demonstrated by the 37 maps in the Klencke Atlas, which was intended as an encyclopaedic summary of the world.

It is almost absurdly huge – 1.75 metres (5ft) tall and 1.9 metres (6ft) wide – and was given to the king by Dutch merchants and placed in his cabinet of curiosities.

"It is going to be quite a spectacle," said Tom Harper, head of antiquarian maps. "Even standing beside it is quite unnerving."

As a contrast, one of the smallest maps in the world, a fingernail-sized German coin from 1773 showing a bird's eye view of Nuremberg, will be exhibited close by.

The exhibition will show how great maps could be as important as great art. Before 1800 – "that's when the rot set in," joked Barber – were you to visit palaces or the homes of the wealthy, maps would have been almost as prominent as paintings or sculptures or tapestries.

They were an important status symbol. Rich men would have a map of the world to show their worldliness; a map of the Holy Land to show their piety; a map of their estate to show their wealth; and a map of their home county or city to show how loyal a citizen they were.

They would also be personalised. For example, a map made in 1582 for Sir Philip Parker of Smallburgh in Norfolk also includes a little Brueghel-esque figure of a man with a monkey on his back: a mocking reference to his recently deceased half-brother Lord Morley, a Catholic and a family embarrassment who "spent his time wandering fairly pointlessly around southern Europe", said Barber. "It is a way of saying 'I'm not like that'."

Barber and Harper have chosen to exhibit maps from more than 4.5m held in the library's collection – the second biggest in the world after the Library of Congress.

Barber said the maps were all made for adornment but "at a deeper level they were made for propaganda. It's all spin. Every map is an exaggeration because you can never 100% capture reality on a reduced surface.

"Up until 1800 people expected maps in these contexts and enjoyed them, but in the course of the 18th century you got the growth of the cult of science, the belief that maps were to do with geography and the only thing that was important was its accuracy."

Barber believes maps are too neglected, particularly by art historians. "In a way we are trying to redress this. The official credo is the only thing that counts about a map is that they are utilitarian objects not really meant for display and that is not the case."

There will also be maps where the propaganda role has been more explicit, such as a Nazi poster produced in Vichy France which shows Churchill as an evil, cigar-chomping sea monster whose attempts to seize Africa and the Middle East were being thwarted by Axis forces, bloodily clipping his tentacles.

Comentários