31 janeiro 2010

29 janeiro 2010

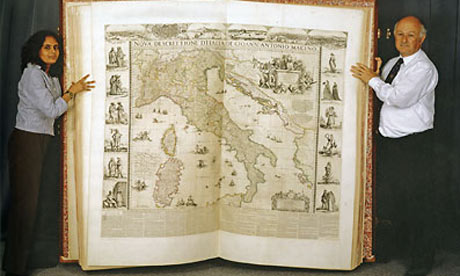

still about Magnificent Maps, the largest BOOK in the world goes on exhibit for the first time

It takes six people to lift it and has been recorded as the largest book in the world, yet the splendid Klencke Atlas, presented to Charles II on his restoration and now 350 years old, has never been publicly displayed with its pages open. That glaring omission is to be rectified, it was announced by the British Library today, when it will be displayed as one of the stars of its big summer exhibition about maps.

The summer show will feature about 100 maps, considered some of the greatest in the world, with three-quarters of them going on display for the first time.

At the exhibition's core will be wall maps, many of them huge, which tell a story that is much more than geography. Many of them, said the library's head of map collections, Peter Barber: "Hold their own with great works of art."

He added: "This is the first map exhibition of its type because, normally, when you think of maps you think of geography, or measurement or accuracy."

The exhibition aims to challenge people's assumptions about maps and celebrate their magnificence, as demonstrated by the 37 maps in the Klencke Atlas, which was intended as an encyclopaedic summary of the world.

It is almost absurdly huge – 1.75 metres (5ft) tall and 1.9 metres (6ft) wide – and was given to the king by Dutch merchants and placed in his cabinet of curiosities.

"It is going to be quite a spectacle," said Tom Harper, head of antiquarian maps. "Even standing beside it is quite unnerving."

As a contrast, one of the smallest maps in the world, a fingernail-sized German coin from 1773 showing a bird's eye view of Nuremberg, will be exhibited close by.

The exhibition will show how great maps could be as important as great art. Before 1800 – "that's when the rot set in," joked Barber – were you to visit palaces or the homes of the wealthy, maps would have been almost as prominent as paintings or sculptures or tapestries.

They were an important status symbol. Rich men would have a map of the world to show their worldliness; a map of the Holy Land to show their piety; a map of their estate to show their wealth; and a map of their home county or city to show how loyal a citizen they were.

They would also be personalised. For example, a map made in 1582 for Sir Philip Parker of Smallburgh in Norfolk also includes a little Brueghel-esque figure of a man with a monkey on his back: a mocking reference to his recently deceased half-brother Lord Morley, a Catholic and a family embarrassment who "spent his time wandering fairly pointlessly around southern Europe", said Barber. "It is a way of saying 'I'm not like that'."

Barber and Harper have chosen to exhibit maps from more than 4.5m held in the library's collection – the second biggest in the world after the Library of Congress.

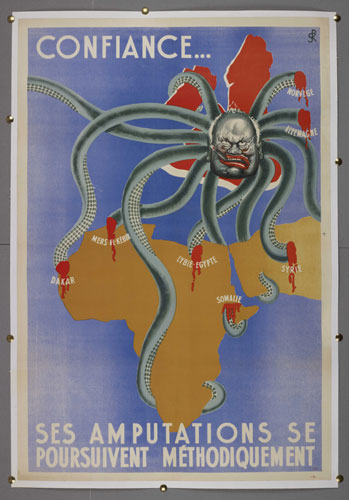

Barber said the maps were all made for adornment but "at a deeper level they were made for propaganda. It's all spin. Every map is an exaggeration because you can never 100% capture reality on a reduced surface.

"Up until 1800 people expected maps in these contexts and enjoyed them, but in the course of the 18th century you got the growth of the cult of science, the belief that maps were to do with geography and the only thing that was important was its accuracy."

Barber believes maps are too neglected, particularly by art historians. "In a way we are trying to redress this. The official credo is the only thing that counts about a map is that they are utilitarian objects not really meant for display and that is not the case."

There will also be maps where the propaganda role has been more explicit, such as a Nazi poster produced in Vichy France which shows Churchill as an evil, cigar-chomping sea monster whose attempts to seize Africa and the Middle East were being thwarted by Axis forces, bloodily clipping his tentacles.

28 janeiro 2010

J.D. Salinger - Did you know Guns'n'Roses and Green Day wrote songs about his masterpiece?

“Catcher in the Rye,” J. D. Salinger’s most famous book, has been a pop-culture icon for a half-century, for better and for worse. Rock-and-roll bands have been particularly attracted to it and to its anti-hero, Holden Caulfield, who has what can only be called a rock-and-roll personality: both passionate and cynical, protective of innocence and drawn to beauty. Artists like Billy Joel, the Offspring, and Old 97s have mentioned the book in their lyrics. Green Day even recorded a song called “Who Wrote Holden Caulfield” on its second album, “Kerplunk.”

Of all the songs written about, against, or in thrall to the work of J. D. Salinger, one of the strangest is one of the most straightforward: “Catcher in the Rye,” by Guns N’ Roses, which appeared on the band’s almost infinitely delayed “Chinese Democracy.” The song appears to be about childhood abuse and the loss of innocence, both themes in the novel, and also about the way that shattered innocence can trigger a cycle of violence. Axl Rose’s lyrics gesture toward the saddest way in which the book is associated with rock and roll, Mark David Chapman’s murder of John Lennon—the book obsessed Chapman, and he was carrying it when he killed Lennon—at the same time that they allude to “Comin’ Thro The Rye,” the Robert Burns poem that Holden Caulfield misreads, giving the novel its title:

And then the voices went away from me

Somehow you set the wheels in motion

That haunt our memories

You were the instrument

You were the one

How a body

Took the body

You gave that boy a gun

The New Yorker

27 janeiro 2010

Valentine

Website

Image courtesy of BoingBoing

Durante a retirada da Rússia na guerra de 1812, os oficiais da cavalaria Valentine e Oscar são separados do pelotão principal por uma brutal nevasca. Eles acham que o que há de pior em meio à neve é a Morte. Ambos não poderiam estar mais errados.

Os dois se deparam com um conflito entre seres mais poderosos do que a humanidade seria capaz de imaginar, um conflito que agora ameaça consumir todo o planeta Terra – porque aqueles que lutavam contra este horror, os poucos bastiões de luz, estão voltando para casa.

Episódio de estréia do aclamado thriller de fantasia em quadrinhos produzido pela roteirista Alex de Campi e pela ilustradora Christine Larsen.

Image courtesy of BoingBoing

During Napoleon’s retreat from Russia in the War of 1812, cavalry officers Valentine and Oscar are separated from the main army by a brutal blizzard. They think the worst thing waiting out there in the snow for them is Death. They could not be more wrong. The two soldiers stumble across an ancient conflict between beings more powerful than humanity can imagine, a conflict which now threatens to consume the Earth and all upon it – because those who have stood in the horror’s path, the few bastions of light, are going home.

Valentine is a fantasy / thriller graphic novel series by writer Alex de Campi and artist Christine Larsen. It is available in 14 languages and counting.

You can’t buy it in a comic book shop because it’s not a traditional comic; it’s a project which has been tailored specifically to be enjoyed on wireless devices: iPhone, Android, e-Readers and of course your laptop. This means rather than pages, we have screens – all the better for optimising viewing on small devices, and adapting to languages which read right-to-left (such as Japanese) as well as left-to-right. On iPhone and Android, we also make use of simple transitions to enhance the reading experience.

The first episode is free. After that, each 65-75 screen episode costs 99 cents, and new episodes come out monthly. However the project is released under a creative commons licence so if you come across a version for free somewhere please do take it and enjoy it with our blessing. If you like it, please recommend it on to friends, or consider tipping us (tip jar at left!) or buying a future episode. We are not a big corporation or a publisher, we are just two women who sometimes can’t even afford groceries.

If you prefer good old paper books to all this wireless malarkey, fret not. When the series is over, we intend to publish it in one big fat digest-size volume. We like books, too, but releasing Valentine episodically like this is a lot of fun for us, and it means we get (hopefully!) a little income and some feedback while working on the series.

Please do get in touch or post if we currently don’t support your language (we are always looking for translators!) or your device. We are working as fast as we can to get Valentine rolled out across most major devices, but sometimes life gets in the way.

Portuguese (prior to the new Spelling Agreement, apparently ;) thanx to Robot Comics

Os dois se deparam com um conflito entre seres mais poderosos do que a humanidade seria capaz de imaginar, um conflito que agora ameaça consumir todo o planeta Terra – porque aqueles que lutavam contra este horror, os poucos bastiões de luz, estão voltando para casa.

Episódio de estréia do aclamado thriller de fantasia em quadrinhos produzido pela roteirista Alex de Campi e pela ilustradora Christine Larsen.

Etiquetas:

Comics Cartoons,

Technotronic,

Translation,

Women

Magnificent Maps - I wanna go see ;)

Opening in April 2010, Magnificent Maps showcases the British Library's unique collection of large-scale display maps, many of which have never been exhibited before. Here the show's curators focus on some of the show's highlights – and explain why maps are about far more than geography

Nazi propaganda, in French!

Nicolo Longobardi / Manuel Dias, Chinese Terrestrial Globe, 1623, wood, lacquer and paint: This, the earliest Chinese globe, was constructed by leading Jesuits for the Chinese Ming rulers, and is believed to have come from an Imperial palace near Beijing. In the collections of western monarchs it would have appeared an exotic and unusual object. But in China too, it would have been very unusual, since it contained western concepts of geography quite at variance with the China-centric nature of contemporary cartography. In its treatment of eclipses and meridians, however, the globe draws on ideas developed in China far earlier than in the west

Gallery at The Guardian

Nazi propaganda, in French!

Diogo Homem, A Chart of the Mediterranean Sea, 1570

Gallery at The Guardian

26 janeiro 2010

Free Rice is feeding Haiti right now

Now featuring even more Subjects to play with:

ART

Famous PaintingsCHEMISTRY

Chemical Symbols (Basic)Chemical Symbols (Full List)

ENGLISH

English GrammarEnglish Vocabulary

GEOGRAPHY

Identify Countries on the MapWorld Capitals

23 janeiro 2010

The first rule of working at home is, you do not talk about working at home.

Priceless, from Jezebel (and do not miss the comments ;)

Yahoo's Shine decided to publish a humor column about the sad realities of working from home. The writers promise "hysterical yet truthful tips to help you stay sane," but their "truths" are generic warnings against getting fat.

Number one is the doozy:

For the love of God and everything we hold dear in this world, do not, I repeat, do not buy sweat pants for comfort while working. You can be just as brilliant in your own damn trousers! I fell under the spell of "well, they are kind of cool black sweats and I did not buy them at Wal-Mart and I could even go walking with them on" line of crap. I don't care if Giorgio Armani designed sweats for his couture line. Do not wear them at home while working. They do have their place – putting laundry in, cleaning out a litter box or 5 but if you sit in front of your computer for 8 to 12 hours a day, you will have develop a HUGE butt and don't get me started on the land where small waistlines go. You need to feel the cold, hard metal of a zipper against your flesh each day of your life.

All the joy of working at home is not having to get dressed. I like yoga pants while working. In fact, people should be happy I'm wearing pants at all.

The rest of the tips are in the same vein.

They Say: "Tell people that you are working from home and suddenly you become the perfect candidate to wait for the cable guy [...] Don't pick up the phone until you see who is calling."

I say: The first rule of working at home is, you do not talk about working at home. The second rule of working at home is, you DO NOT talk about working at home.

I say: The first rule of working at home is, you do not talk about working at home. The second rule of working at home is, you DO NOT talk about working at home.

They Say: "Regardless of the weather, open the front door, crack open a window and escape. Don't put it off until later in the day because you know damn well you won't do it."

I say: Didn't you read the internet? The zombie apocalypse could break any day now - spending long periods in the house with nothing but canned goods is strategic preparation.

They Say: "You can wash dishes, empty garbage cans, shred documents, and take bathroom breaks while you're on the phone getting your next assignment from those who think working at home = free time."

I say: If you have ever tried to use the bathroom while talking to your boss, you know that this rarely ends well. Either you fuck up the timing on the mute or they ask you a question mid-stream. Partial solution: flush later. And figure out if this is a loud pee, a quiet pee, or something you shouldn't be on the phone for.

I say: Didn't you read the internet? The zombie apocalypse could break any day now - spending long periods in the house with nothing but canned goods is strategic preparation.

They Say: "You can wash dishes, empty garbage cans, shred documents, and take bathroom breaks while you're on the phone getting your next assignment from those who think working at home = free time."

I say: If you have ever tried to use the bathroom while talking to your boss, you know that this rarely ends well. Either you fuck up the timing on the mute or they ask you a question mid-stream. Partial solution: flush later. And figure out if this is a loud pee, a quiet pee, or something you shouldn't be on the phone for.

They Say: " Cleanliness is next to impossible if you don't bathe."

I say: If I have stinky armpits from working on crazy deadlines for twelve hours straight, other apartment dwellers will have to deal. And why are they so close to me before I shower anyway?

I say: If I have stinky armpits from working on crazy deadlines for twelve hours straight, other apartment dwellers will have to deal. And why are they so close to me before I shower anyway?

22 janeiro 2010

"There is no Beat Generation ... just a bunch of guys trying to get published"

The opening film at Sundance is a prestigious position to be in: Robert Redford introduces the film, stars are in attendance, and as a result it can be difficult to score tickets. This year was no different with people lining the sidewalk to the theater holding signs asking for extra tickets. However, if you look back at the opening night film for the past few years, you can see that it has never ended up being the most buzzed-about film at the festival: Riding Giants (2004), Happy Endings (2005), Friends With Money (2006), Chicago 10 (2007), In Bruges (2008), and Mary & Max (2009).

Unfortunately, HOWL is in the same boat. And to paraphrase Ginsberg himself: There is no HOWL ... it's just a bunch of scenes trying to be a movie. Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (The Times of Harvey Milk, The Celluloid Closet) have moved beyond their normal documentary subjects and tackled the dubious task of turning a classic poem into a feature film, and it falls far short for several reasons. It might have been the hot ticket for opening night, but it got Sundance 2010 off to an extreme clunky start.

Howl wants to be three different movies: a dramatization of the court case deciding whether the publication of the poem was obscene or not, reenacted interviews with Ginsberg reflecting on Howl and the trial, and animated segments meant to picture the poem itself. The trouble is that none of them work on their own, and when you mash them together, you just end up with the three cooks who spoiled the soup. Three things that don't work on their own add up to one big thing that becomes triply unengaging.

The court case is bland (although it does provide a few laughs), with Jon Hamm doing his best Don Draper as the defense attorney. The animated segments use very amateurish CGI set to jazz music as a singular vision of the poem ... which just doesn't work at all. Why would you try so hard to illustrate what people picture when they hear or read HOWL? It would be like someone trying to tell you what you should see in your head when you listen to Mozart. The interview segments are the most appealing, but they boil down to Franco basically parroting back recorded conversations between Ginsberg and an unseen journalist.

Ginsberg's personal life is barely touched on in the film, with fleeting glimpses of his job in advertising, his time with Jack Kerouac, or his longtime partner Peter Orlovsky. It was as if the filmmakers decided everything biographical had to be crammed into five minutes of total screentime so the rest of the film could focus on courtroom drama and animation. Or dramatic readings by Ginsberg (in black and white, to boot) of HOWL in coffee shops with extremely excited extras nodding their approval in the audience. To be fair, Franco does a decent job in the role when he's imitating Ginsberg via recordings, but veers off-track in fictionalized moments.

Oddly enough, HOWL began life in the Sundance labs a year ago as a documentary, and that would have been tremendously more engaging. There's a brief scene at the end of the film featuring the actual Ginsberg singing one of his poems, and it makes you ache for more archival footage of the author. Interviews discussing the impact of HOWL, photos, recordings (a vintage recording of Ginsberg reading HOWL aloud was actually discovered in 2007), and more of a background would have been more interesting to watch than this unfortunately clumsy approach to adapting one of the quintessential American poems to film.

Unfortunately, HOWL is in the same boat. And to paraphrase Ginsberg himself: There is no HOWL ... it's just a bunch of scenes trying to be a movie. Directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (The Times of Harvey Milk, The Celluloid Closet) have moved beyond their normal documentary subjects and tackled the dubious task of turning a classic poem into a feature film, and it falls far short for several reasons. It might have been the hot ticket for opening night, but it got Sundance 2010 off to an extreme clunky start.

Howl wants to be three different movies: a dramatization of the court case deciding whether the publication of the poem was obscene or not, reenacted interviews with Ginsberg reflecting on Howl and the trial, and animated segments meant to picture the poem itself. The trouble is that none of them work on their own, and when you mash them together, you just end up with the three cooks who spoiled the soup. Three things that don't work on their own add up to one big thing that becomes triply unengaging.

The court case is bland (although it does provide a few laughs), with Jon Hamm doing his best Don Draper as the defense attorney. The animated segments use very amateurish CGI set to jazz music as a singular vision of the poem ... which just doesn't work at all. Why would you try so hard to illustrate what people picture when they hear or read HOWL? It would be like someone trying to tell you what you should see in your head when you listen to Mozart. The interview segments are the most appealing, but they boil down to Franco basically parroting back recorded conversations between Ginsberg and an unseen journalist.

Ginsberg's personal life is barely touched on in the film, with fleeting glimpses of his job in advertising, his time with Jack Kerouac, or his longtime partner Peter Orlovsky. It was as if the filmmakers decided everything biographical had to be crammed into five minutes of total screentime so the rest of the film could focus on courtroom drama and animation. Or dramatic readings by Ginsberg (in black and white, to boot) of HOWL in coffee shops with extremely excited extras nodding their approval in the audience. To be fair, Franco does a decent job in the role when he's imitating Ginsberg via recordings, but veers off-track in fictionalized moments.

Oddly enough, HOWL began life in the Sundance labs a year ago as a documentary, and that would have been tremendously more engaging. There's a brief scene at the end of the film featuring the actual Ginsberg singing one of his poems, and it makes you ache for more archival footage of the author. Interviews discussing the impact of HOWL, photos, recordings (a vintage recording of Ginsberg reading HOWL aloud was actually discovered in 2007), and more of a background would have been more interesting to watch than this unfortunately clumsy approach to adapting one of the quintessential American poems to film.

a Cinematical review

Etiquetas:

literature,

Men,

Movie Buff and Couch Potato

21 janeiro 2010

19 janeiro 2010

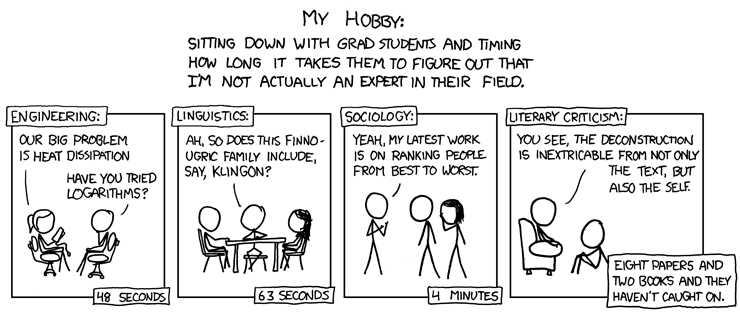

AVATAR: My thoughts (pretty much) exactly ;)

From Ben, commenting on a post at The Millions:

All your remarks about the film’s various failings seem accurate. You must be aware, though, that 95% of the human race–specifically the 95% with magic in their souls–will disagree with you. I think Avatar might better be described as a ride than a film. Our investment in the outcome of on-screen conflict and struggle derives less from identification with fleshed-out characters and politically nuanced themes (the classical tools) than from a very physical, embodied sense of placement in the action, which ends up yielding powerful emotional identification anyway. The sacrificed element, and the element on which you concentrate most of your review, is memorability. There is very little, afterward, to talk about. Narrative, dialogue, anything that persists in word-memory, which is mostly what we’ve got. This is a film of pure sensation. But it seems clear to me–it’s borne out both by the critical reception the film has received and its ongoing box-office success–that Avatar is extremely successful at imparting the sensation of elevated wonder it sets out to impart. And I have no problem with a juggernaut of wonder-creation like this promoting a simple message of environmentalism and anti-imperialism. I think the case could even be made that the utter schematic simplicity of the framing moral struggle, its reliance on comfortable archetypes of accepted mythic power, allows a kind of total submission to sensation hard to achieve when the critical faculty is more actively engaged. The tight correspondence of Pangea-creatures to Earth-creatures or myth-creatures (horse, bull, big red dragon) is probably deliberate. Our immersion in Avatar-as-embodied-experience relies on the presence of familiar anchor points–most obviously, we have to find the Na’vi super hot. The writing was shitty, no question, but mainly just in being so bland. It was never enough to throw me out of the story. In fact, I think dry cleverness of the kind that generated iconic lines in T2, Jurassic Park, etc would have been out of place here, just as it would have been out of place in Princess Mononoke, another environmental parable that traffics in elevated wonder (although with far more subtlety and ambiguity). If the writing were good, Avatar could have been much more enjoyable for the class of viewers who pay close attention to that. Future films that reach this level of visual imagination and accomplishment might actually be memorable, too, at which time Avatar might be recalled as a kitschy artifact of the early days of 3D. But this was seriously one of the best rides I’ve ever gone on, and I’m really glad I was able to suspend whatever needed suspending in order to get my $16 worth, because, damn, $16.

P.S. You have no magic in your soul, you crotchety bastard. When the giant spinning machines of industry are closing in on the heart of the forest, are you really thinking “poor strategic planning, should be dropping logs”???

P.S. You have no magic in your soul, you crotchety bastard. When the giant spinning machines of industry are closing in on the heart of the forest, are you really thinking “poor strategic planning, should be dropping logs”???

From Ryan at Freshman Denial:

The Top 5 Reasons People Say Avatar Sucks (And Why They’re Wrong)

5. Unobtanium is a stupid name for that element.

(...)

4. The characters are flat and one-dimensional.

(...)

3. The dialogue is campy and corny and bad.

(...)

2. The acting was bad.

(...)

1. The plot is cliche and predictable.

This is probably the most common piece of criticism I have heard regarding the film. I hear it over and over, and continually I repeat: a cliche story in an imaginative new universe with new characters, a new setting, and a plethora of mind-blowing intricacies ceases to be negatively cliche.

(...)

Etiquetas:

Movie Buff and Couch Potato,

Technotronic

Science fiction is as much a reflection of society's deep fascination with science as it is an agent of change for its future course

In 1984, William Gibson coined a word—“cyberspace”— and used it in a science fiction novel. At the time, few people had a concept of what such a term could mean. And yet, thanks to Gibson’s use of it, especially in his epochal cyberpunk book Neuromancer, “cyberspace” gradually gained enough cultural credence to become the de facto name for the emerging World Wide Web.

Today we unthinkingly use the word to refer to an everyday experience that didn’t even exist when Neuromancer was penned—but one which is arguably similar to Gibson’s vision of a “consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators.” Of course, it’s unclear whether Gibson primed the pump for the widespread acceptance of advanced communications technologies, or if he merely pointed out the tip of an iceberg ready to emerge from the waters of a high-tech subculture.

What is clear is that science fiction plays an essential role in the dissemination and popularization of science’s most nascent and speculative concepts. In the 1980s, when we were introduced to a fictional “cyberspace,” we digested the idea to the point of banality, and in the process unwittingly prepared ourselves for massive cultural and technological change.

Does our collective dreaming, our technolust, and our romance for the stars shape the way we understand future scientific advances? More importantly, can it change the future?

In a word, yes.

Ever since the 19th-century scientific dreams of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, science fiction has been a future-changing medium. Although its role is not necessarily to be prophetic, it often fulfills its own predictions in surprising ways. We literally live in a science-fictional world. Ideas that seemed like ludicrous fantasies in sci-fi’s “golden age” of the 1950s have long since become reality: geosynchronous communications satellites, famously dreamed up by Arthur C. Clarke; Karel Capek’s “robots,” first concocted in 1920; or cloning and neuro-enhancing pharmaceuticals, the subject of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World from 1931.

It may even be that the romances presented by sci-fi authors—such as Clarke’s and Kapek’s inventions and the techno-dystopias of 1980s cyberpunk—mellowed the sting of cultural change. Those stories turned the unloved margins of scientific research and the Gordian complexity of computer engineering into things that can be more easily understood, related to, or even romanticized. They have allowed us to dream about new realities, and to feel invested in science even if (and when) we don’t understand it. By seeing a version of the future worked out in the incubator of sci-fi, we can begin to appreciate the myriad possibilities of science—as well as explore the potential negatives of its unintended consequences.

Sci-fi narratives articulate our current global concerns in convincing—and often dramatic—ways. Although hyperbolic, recent blockbusters WALL-E and Avatar wrestle with the very real issues of sustainability, scarcity, and ecosystem collapse, as did the landmark novel Ecotopia a generation previous. Brave New World (and the H.G. Wells story that inspired it, Men Like Gods) along with countless other sci-fi plots, attempts to reconcile the vast promise of science—cognitive enhancement, gene therapy, artificial intelligence—with important ethical and social considerations inherent in their potential. Stitched into the fantasy worlds of almost all good science fiction are reflective threads that mirror and confront some of the greatest challenges of our time. Such considerations signal a movement toward increased responsibility, especially among the youngest generations, for thinking critically about the future. As the critic Robert Scholes wrote, “to live well in the present, to live decently and humanely, we must see into the future.”

Imagining our future changes our perspective. As such, science fiction has long provided its writers remarkable leverage for political and social commentary. Some craft it more incisively than others—the bulk of 1950s Western sci-fi could be summed up with the statement, “the aliens are Russians.” And yet, throughout its short history, science fiction has touched on practically every major sociopolitical theme throughout world history. When the writers of classic Star Trek episodes created conflicts between the polyester-suited crew of the Enterprise and a rotating cast of alien life, the subtext was immediate: race relations, Cold-War fears, and American imperialism. What kind of long-term effect this had on the political consciousness of its watchers is difficult to judge, but such engagement with complicated social issues is not a rarity in the genre; it’s the norm.

The best art takes our fears, hopes, and anxieties and frames them in a form that provides long-lasting meaning and value. Critics largely ignore these qualities in sci-fi, disregarding it as “genre” fiction in the domain of Harlequin romances and “true crime” novels. While many people love science fiction, as the pedigrees of some of the top-grossing movies of all time attest, much fewer consider it to be a potential vessel for long-lasting value.

The problem is that many negative misconceptions about sci-fi are at least partly true. It is a form that traditionally privileges story over style. A great deal of science fiction is schlocky, impenetrable, or innocuous. All of this is true—and yet totally irrelevant. As the writer and critic Damon Knight once noted, “if science fantasy has to date failed to produce much great literature, don’t blame the writers who have worked in the field; blame those who, out of snobbery, haven’t.”

And after that blame has been passed, look again. In sci-fi, ideas often take precedence over form, which can be a great advantage. It is, after all, a literature of ideas—wild ideas that infect the world with wonder, speculation, and the shock of estrangement. On my sagging bookshelf of paperbacks, I have androids, floating ecosystems in space, secret drugs, tyrannical computers, and body-snatchers. I have one million years of the future, sentient clouds, and talking newts. I have entire experimental worlds, rich with notions that are as independent from the mainstream lexicon as they are unencumbered by its literary norms.

We can’t overestimate the merits of science fiction—nor its ability to affect the world. Isaac Asimov observed that, “science-fiction writers and readers didn’t put a man on the Moon all by themselves, but they created a climate in which the goal of putting a man on the Moon became acceptable.” Are we to assume that writers will not continue to create such climates? What will the next “cyberspace” be, or the next Moon landing, and who will invent it? Science-fiction writers in the year 2050 will be imagining the year 3000, and beyond, and so on. It’s a living, breathing tradition that informs the very world it critiques, inventing new myths, words, and realities just as we catch up to its old ones. Our greatest science-fiction writers feed the future with speculation as we move towards it, and we are all better off for considering what they have to say.

Etiquetas:

booooooks,

there are no limits to science

16 janeiro 2010

15 janeiro 2010

Make a Font from your Handwriting (alas, not me... :)

It’s craft Saturday here at TheNextWeb. Given that there is probably nothing more to do than wait for new Daily Show episodes to come out, why not give your creative hand a shake? Let’s make a font.

The process is actually quite simple, and free. FontCapture is a great little app that will allow you to do this in less than ten minutes, if you have a scanner. Head to FontCapture.com, and print out the form .pdf. Then fill in all the boxes on the form with your own handwriting.

Quick warning, use a felt pen of some sort. Pens did not work well in my testing. Once you have filled out the form, scan it, then name and upload the image. Once you submit the scanned page, it should take around a minute for the font to be generated. On Windows 7, download and open the file, and then just click install. Wordpad will find it right away.

The process is actually quite simple, and free. FontCapture is a great little app that will allow you to do this in less than ten minutes, if you have a scanner. Head to FontCapture.com, and print out the form .pdf. Then fill in all the boxes on the form with your own handwriting.

Quick warning, use a felt pen of some sort. Pens did not work well in my testing. Once you have filled out the form, scan it, then name and upload the image. Once you submit the scanned page, it should take around a minute for the font to be generated. On Windows 7, download and open the file, and then just click install. Wordpad will find it right away.

Don Quixote project aims to put epic tale on Twitter

He was the hero of hopeless causes and the defender of imaginary damsels. Now fans of Don Quixote, the Spanish literary character who tilted at windmills, are embarking on an appropriately quixotic challenge – to put the entire contents of Don Quixote de La Mancha on the Twitter microblogging site.

The Twijote project, as it is known, aims to publish the 470-odd pages of the first volume of Don Quixote's adventures using just the 140-character blocks of text allowed by Twitter. It has set itself strict rules, of the honourable but potentially foolish kind that Don Quixote and his creator, Miguel de Cervantes, might have approved of.

The 8,200-odd tweets needed to get to the end of the first volume must come from one-off visitors to the Twijote site. They are given the next block of 140 characters of text to put on Twitter.

"We reckon it will take about a year, if people stick with it," said Pablo López, a web designer from the north-western Spanish city of Vigo who thought up the project. "The idea is to show that culture can exist in social media – that it is not just a place for nerds and freaks," he said.

Twijote has no sponsors and no ambition to make money. "It is something we put up to see what would happen," said Lopez, who pulled in web designers from his company to help. "I had the idea one day and came into the office and persuaded people it was worth doing."

Volunteers have signed on from all over Spain and Latin America, with visitors also arriving from non-Spanish speaking countries such as Finland.

Lopez pointed to other literary adventures in Twitterland, including the Serial Chicken novel being published in instalments by Spanish writer Jordi Cervera.

English-language literary Twitter projects include selected musings from Samuel Pepys' 17th century diaries and snippets from the books published in mini-instalments by e-mail and on the internet.

14 janeiro 2010

The Virgin Mary in Easter Eggs - all things Ukrainian ;)

Ukrainian artist Oksana Mas has created an unusual mosaic portrait of the Virgin Mary, using 15,000 painted Easter Eggs.

Unveiled yesterday, inside the gorgeous Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, the giant mosaic weighs 2.5 tons and is made out of 15,000 wooden Easter Eggs. Oksana Mas started working on her masterpiece nine months ago, painting the eggs all by herself, but later children from all across the country got involved and helped out with the painting. The Easter-egg portrait of the Virgin Mary, by Oksana Mas, measures 7×7 meters.

Unveiled yesterday, inside the gorgeous Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, the giant mosaic weighs 2.5 tons and is made out of 15,000 wooden Easter Eggs. Oksana Mas started working on her masterpiece nine months ago, painting the eggs all by herself, but later children from all across the country got involved and helped out with the painting. The Easter-egg portrait of the Virgin Mary, by Oksana Mas, measures 7×7 meters.

13 janeiro 2010

12 janeiro 2010

A History of Sin - new translation!

WITH 'values' on everyone's lips, this book provides some much-needed background, from the Stone Age onwards. Cultural context has always determined our moral habits, which is why prescribing them without serious thought can end in upset.

What, for example, are we to make of Oliver Thomson's example of the 300 French prostitutes who, accompanying the Third Crusades, 'dedicated as a holy offering what they kept between their thighs'? Or the Spartan code which called for 'the early practical application of eugenics' to cull offspring unsuitable for military service? Or the sect which believed chewing cannabis brought them closer to God? It is easy to find legitimating examples of things disapproved of today. And this bears out Thomson's main point, that 'morality is subject to fashion'.

The catalogue of the purportedly sinful is enormous, and it would be easy for readers of this book to be bogged down, had Thomson not first provided a rough analytical framework to regulate the mass of information he turns up. This initial section covers the genesis of moralities, the causes of moral differences, motivations and sanctions, moral training and propaganda, myths and fables, and so on. He then enumerates the moral characteristics of individual epochs. For example, we learn that in medieval times there was 'a grete multiplicacyon of orrible syn amongst syngle women'.

It is interesting, in a vicarious sort of way, to read of the excesses of tyrants from Henry VIII to Idi Amin. But the book is ultimately unsatisfying. Part of the problem is that Thomson whips the carpet out from under his own feet: plainly, if the thesis is that you can't define sin in any absolute, trans-

epochal way, how can you have a history of sin? Sin, as we understand it, is a relatively recent, Judaeo-Christian invention. The Greeks, for example, didn't have a concept of sin, basing their morality around something nearer to what we would call shame.

What we call it is in fact the issue, and this is the other main fault of Thomson's book: it doesn't come to terms with language, the very material with which we prescribe and describe moral behaviour. Language in its most extended sense may include the flicker of images coming off video and computer-game screens, and it sometimes seems as if such language were having a fragmentary effect on grand ideas like 'truth' and 'justice'.

Thomson's conclusion is that many of the great injustices of the world have been perpetrated in the name of justice, and many of history's greatest untruths uttered in the name of truth. He suggests that it is time we moved towards a 'new, mature ethos' with room for everyone's views. Oddly enough (though Thomson doesn't mention it), electronic media would be exactly the appropriate form in which to convey such pluralistic morality. But then again pixilated prophets don't have quite the same authority as ones carrying tablets of stone.

The Independent Book Review

Éric Rohmer, RIP

Thanx to The Guardian, Éric Rohmer's career in clips:

Rohmer's first feature was a pure-blood product of the burgeoning French New Wave; a loose-limbed, low-budget tale of poverty-row Paris, evocatively played out in the Latin Quarter as its hero rattles between the houses in search of loot. The film was destined to be eclipsed by the likes of Breathless and The 400 Blows – but Rohmer had yet to find his perfect rhythm.

The third of Rohmer's six "moral tales" offers a wry and playful battle of the sexes, as the nymphet of the title makes a point of bedding a different man each night – and dances constantly away from the two male friends who try to tame her. Its St Tropez setting showed how Rohmer was as comfortable in France's wide open spaces as in the bustling metropolis.

Jean-Louis Trintignant gives a superb performance as the Catholic engineer who finds himself mentally and emotionally (if not quite physically) undone by the smart, cerebral Maud (Francoise Fabian) in what is arguably the most iconic of all Rohmer's dramas. My Night With Maud is a film that shows how simple conversation can be as purely sensual – and as erotically charged – as actual sex. Here, perhaps, is the movie that taught Richard Linklater all he knows.

Rohmer cemented his credentials as the great poet of bourgeois repression with Claire's Knee, in which a buttoned-up businessman finds himself smitten by the sight of a bare limb while on vacation. As the hero's world collapses around him, Rohmer shows his trademark light touch to keep all the pieces revolving in the air – turning each periodically to the sunlight so we can view them better.

The Green Ray marries social realism with the fantasy stylings of the fairy tale, concocting a haunting essay on female loneliness around a Parisian secretary who finds herself abandoned for the summer. Nobody was as good at Rohmer at conjuring epiphanies out of the everyday. None of his films ends on quite so magical a note as this sun-dappled little treasure.

A Summer's Tale, fittingly enough, was to prove the warmest and most seductive of Rohmer's Tales of the Four Seasons. It's the story of a young student (Melvil Poupaud) who finds himself torn between a trio of girls as he bounces around the coastline of Brittany. Now nudging into his dotage, the director belied his age with a supple, langorous and oddly poignant tale of youthful follies.

Towards the end of his life, Rohmer risked alienating his fan base by breaking away from fine-tuned, contemporary dramas and turning his gaze to the films of the past. He made his film swansong with The Romance of Astrea and Celadon: an adaptation of Honoré d'Urfé's 17th-century pastoral novel of fifth-century Gaul, complete with shepherds, nymphs and druids chatting on courtly love. It was a curious venture, but an oddly intoxicating one. This was a romance that crept up on you, full-hearted evidence that even at the age of 87, here was a director still making unique films. It was a worthy last work of a one-off talent.

Etiquetas:

Men,

Movie Buff and Couch Potato,

Vive la France

10 janeiro 2010

Oh, yes, Viggo, you did, bless you ;)

Did I say that?

ON BEING VOTED THE SEXIEST MAN ALIVE

So there are a lot of dead men who are sexier? (2006)

ON TREES

I look at them as I look at people. I get along well with most trees. If I get into arguments with them, it's probably my own fault (2008)

ON BEING HOT PROPERTY

I've been told I've arrived so many times, I don't know where I ever went (1999)

ON NOT WINNING AN OSCAR FOR "EASTERN PROMISES"

Ninety-nine per cent of the [other] losers didn't want to do the losers' dance with me. They also sort of ran from me like I was some shitfaced drunk (2009)

ON HIS PAINTINGS

A couple of days ago, l looked at all of them and I was like, "I don't know what these are." Then it snowballed: "What kind of actor am I anyway? What kind of father? God, I'm such a vain, self-involved creature, and I should just stop making these things and inflicting them on people!" I can see why people jump out of windows (1999)

ON MISSING HIS HORSES WHILE AWAY FILMING

They're terrible at writing letters (2006)

ON LIFE'S LITTLE PLEASURES

I usually pee outside my house. There's nothing nicer than peeing at night, looking at the stars, smoking a cigarette (2009)

ON LOSING SOME OF HIS POEMS

There is no point in trying to remember and rebuild the word houses, word hills, word dams and word skeletons (2004)

ON NUDITY

I don't mind doing nude scenes in movies. Actors who say they do are lying (2001)

ASKED HIS FAVOURITE JOKE

Me (2009)

HIS POEM "CHACO"

"I shit in the forest / like the monkeys / with their teeth / perfect and yellow / having no fear / of any tiger" (1995)

WHILE MAKING THE FILM "PRISON"

After this movie wraps, I'm thinking of going into goat-herding, like my mother and her mother before her (1987)

TO ELVES ON THE SET OF "LORD OF THE RINGS"

When you are done with your nails, we are being attacked (2001)

ON THE INVASION OF IRAQ

It was obvious to everyone that it was a movie that was green-lit (2004)

ASKED WHERE HE'S BASED

Planet earth – mostly (2008)

09 janeiro 2010

08 janeiro 2010

Translation Prizes, UK edition - (Saramago's translator) Margaret Jull Costa, wins for Bernardo Atxaga - Miguel Sousa Tavares translator Peter Bush, wins for Equator

Bernardo Atxaga writes in Basque and Spanish. The Accordionist’s Son was published in Basque in 2003 as Soinujolearen Semea and then translated into Spanish as El hijo del acordeonista by Asun Garikano and the author. This is the version that Margaret Jull Costa, the winner of the Premio Valle Inclán, has rendered into fluent colloquial English. Reviewing the Basque edition (TLS, August 13, 2004), Amaia Gabantxo described it as a “self-referential, multilayered work” that “offers a lyrical yet harsh view of what happened in the Basque country after the Spanish Civil War”, when the men of the new generation were driven into the arms of ETA. The book is, in Gabantxo’s estimation, “the first great Basque novel”.

Earlier Peninsular history is the theme of Miguel Sousa Tavares’s novel, Equator. The book is partly set on the Portuguese island colony of São Tomé, to which the hero has been sent, in 1905, by King Dom Carlos as its new governor. [Sousa] Tavares concocts a brew of sex and colonial and slave history, in which Portugal’s “oldest ally” vies for the spoils. Reviewing the book, Toby Lichtig (TLS, November 21, 2008) described the sex in the book as “copious and mawkish”, while noting that Peter Bush’s “occasionally clotted translation” rose to the “challenge with gusto”. Bush, who until now has translated Spanish fiction, wins the biennial Calouste-Gulbenkian Foundation Prize for translation from the Portuguese.

[and I can't find information about this Gulbenkian prize...]

Why I prefer The Mookse and the Gripes book review website, or the differences between «savage» and «wild»

- Question for Chris: You mentioned “Wild Detectives,” and I’ve wondered about that, because I know Borges translated Faulkner’s “The Wild Palms” as “Las Palmeras Salvajes.” Do you think that’s a better translation than “Savage” and do you have any inside scoop about why they went with “Savage Detectives”?»

- Hi Damion, I’m not sure Chris Andrews checks this blog regularly or even if he comes here any more. I’d like to think he does in between translating more Aira, but maybe not. Because you might not get a response from him, I’ll invite anyone with knowledge to answer your questions. And I’ll try to answer it in my own way as well — I’m fluent in Portuguese and proficient in Spanish, though I’m no translator. Any other thoughts are very welcome.

I’ve never read The Savage Detectives, so this is not my opinion on whether “savage” or “wild” is more correct when applied to Bolaño’s book. I think both Mr. Andrews and Ms. Wimmer are exceptional translators, and I’m not even sure if it was Ms. Wimmer or the publisher who chose the title. My words here are more of an exploration. You can determine whether “savage” was le mot juste.

When I first arrived in Brazil, I remember hearing about all of the “savage” (“selvagem”) animals. I was in the Amazon area, so I assumed “selvagem” connoted what “savage” does in contemporary English, something dangerously wild and uncontrollable, something coldly vicious. Then someone said they had a cat that was “selvagem,” and I learned that in Portuguese the word “selvagem” (and in Spanish the word “salvaje”) is often used in the same way we in English use “wild” to mean untamed, feral, or even undomesticated (I have an idea that undomesticated, with its connotations of homelessness and wandering, might work well in Bolaño’s book). None of those words necessarily mean vicious or cold. But then again, neither does savage, particularly as it used to be used. Its great to see what baggage words pick up over the years.

Whether “savage” was used because it fits the text or whether it was used because it is more marketable, I don’t know. It does sound a bit more compelling than “The Wild Detectives,” though, doesn’t it? But even if “savage” is wrong because it connotes the wrong meanings in English, “The Wild Detectives” might not connote in English the same ideas as “salvaje” does in Spanish. I might think of unruly as opposed to feral if “wild” were used.

Nobel prizewinners battle for Translation prize - there's Brazilian Portuguese, at least...

A misguiding post title, since those Nobel winners didn't translate anything themselves...

Three Percent ( 3% of books published in the US are works in translation):

After months and months (twelve to be exact) and books upon books, our nine fiction panelists finally came up with the 25-title fiction longlist for this year’s Best Translated Book Award.

It was a rather difficult decision—it always is, and for me, there’s always a moment where it seems like 30 books would be a better number than 25 . . . —but I’m personally really happy with the list that we came up with. There are some classic authors (Robert Walser, Robert Bolano), some relative unknowns (Wolf Haas, Ferenc Barnas, Cao Naiqian), and a nice geographical mix (including books from Egypt and Djibouti).

Over the next few days, we’ll be highlighting some anthologies, retranslations/reprints, and honorable mentions that didn’t make the longlist. Then, starting next Monday and running for 25-consecutive business days, I’ll highlight a title a day building up to Tuesday, February 16th when we’ll announce both the fiction and poetry finalists for the 2010 Best Translated Book Awards.

One interesting thing about this year’s fiction longlist—it’s incredibly diverse. We have authors from 24 different countries, writing in 17 different languages, and published by 15 different publishers . . .

Without further ado, here are the 25 fiction finalists. Click on the title to purchase the book from Idlewild Books—our featured indie store of the month—or click on the publisher’s name to go to the dedicated page on the publisher’s website.

2010 Best Translated Book Award: Fiction Longlist

The Ninth by Ferenc Barnás.

Translated from the Hungarian by Paul Olchváry. (Hungary)

(Northwestern University Press)

Translated from the Hungarian by Paul Olchváry. (Hungary)

(Northwestern University Press)

Anonymous Celebrity by Ignácio de Loyola Brandão.

Translated from the Portuguese by Nelson Vieira. (Brazil)

(Dalkey Archive)

Translated from the Portuguese by Nelson Vieira. (Brazil)

(Dalkey Archive)

The Skating Rink by Roberto Bolaño.

Translated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews. (Chile)

(New Directions)

Translated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews. (Chile)

(New Directions)

Every Man Dies Alone by Hans Fallada.

Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. (Germany)

(Melville House)

Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. (Germany)

(Melville House)

Vilnius Poker by Ričardas Gavelis.

Translated from the Lithuanian by Elizabeth Novickas. (Lithuania)

(Open Letter)

Translated from the Lithuanian by Elizabeth Novickas. (Lithuania)

(Open Letter)

The Zafarani Files by Gamal al-Ghitani.

Translated from the Arabic by Farouk Abdel Wahab. (Egypt)

(American University Press of Cairo)

Translated from the Arabic by Farouk Abdel Wahab. (Egypt)

(American University Press of Cairo)

The Weather Fifteen Years Ago by Wolf Haas.

Translated from the German by Stephanie Gilardi and Thomas S. Hansen. (Austria)

(Ariadne Press)

Translated from the German by Stephanie Gilardi and Thomas S. Hansen. (Austria)

(Ariadne Press)

The Confessions of Noa Weber by Gail Hareven.

Translated from the Hebrew by Dalya Bilu. (Israel)

(Melville House)

Translated from the Hebrew by Dalya Bilu. (Israel)

(Melville House)

The Discoverer by Jan Kjærstad.

Translated from the Norwegian by Barbara Haveland. (Norway)

(Open Letter)

Translated from the Norwegian by Barbara Haveland. (Norway)

(Open Letter)

Memories of the Future by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky.

Translated from the Russian by Joanne Turnbull. (Russia)

(New York Review Books)

Translated from the Russian by Joanne Turnbull. (Russia)

(New York Review Books)

There’s Nothing I Can Do When I Think of You Late at Night by Cao Naiqian.

Translated from the Chinese by John Balcom. (China)

(Columbia University Press)

Translated from the Chinese by John Balcom. (China)

(Columbia University Press)

The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk.

Translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freely. (Turkey)

(Knopf)

Translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freely. (Turkey)

(Knopf)

News from the Empire by Fernando del Paso.

Translated from the Spanish by Alfonso González and Stella T. Clark. (Mexico)

(Dalkey Archive)

Translated from the Spanish by Alfonso González and Stella T. Clark. (Mexico)

(Dalkey Archive)

The Mighty Angel by Jerzy Pilch.

Translated from the Polish by Bill Johnston. (Poland)

(Open Letter)

Translated from the Polish by Bill Johnston. (Poland)

(Open Letter)

Death in Spring by Mercè Rodoreda.

Translated from the Catalan by Martha Tennent. (Spain)

(Open Letter)

Translated from the Catalan by Martha Tennent. (Spain)

(Open Letter)

Landscape with Dog and Other Stories by Ersi Sotiropoulos.

Translated from the Greek by Karen Emmerich. (Greece)

(Clockroot)

Translated from the Greek by Karen Emmerich. (Greece)

(Clockroot)

Brecht at Night by Mati Unt.

Translated from the Estonian by Eric Dickens. (Estonia)

(Dalkey Archive)

Translated from the Estonian by Eric Dickens. (Estonia)

(Dalkey Archive)

In the United States of Africa by Abdourahman Waberi.

Translated from the French by David and Nicole Ball. (Djibouti)

(University of Nebraska Press)

Translated from the French by David and Nicole Ball. (Djibouti)

(University of Nebraska Press)

The Tanners by Robert Walser.

Translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky. (Switzerland)

(New Directions)

Translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky. (Switzerland)

(New Directions)

Etiquetas:

literature,

the world is my oyster,

Translation

Les montres les plus compliquées du monde

My bold formatting - and why?

Because Lisbon was and is the true continental Finisterre :)

Because Lisbon was and is the true continental Finisterre :)

Leroy 01

En 1876, une montre extra-compliquée fut construit, pour M. le comte Nicolas Nostitz, de Moscou, et fut vivement admirée à l'Exposition universelle de Paris (1878). Elle comportait onze complications mécaniques dont voici l'énumération:

1° Le quantième des jours; 2° Le quantième des dates; 3° Le quantième des mois et années bissextiles; 4° Les phases et l'âge de la lune; 5° La seconde indépendante et rattrapante; 6° Le compteur d'heures; 7° Le compteur de minutes 8° La seconde foudroyante; 9° La répétition des heures, quarts et minutes; 10° Les longitudes des principales villes d'Europe et d'Asie; 11° Les longitudes des principales villes d'Europe et d'Amérique, visibles sur un cadran de rechange.

Lorsque M. le comte Nicolas Nostitz mourut, cette belle montre échut en héritage à M. le général comte Nostitz, son frère, qui la céda, en 1896, à M. A.-A. de C. M., grand amateur d'horlogerie et possesseur d'une des plus importantes collections de montres qui existent. En amateur avisé, M. A.-A. de C. M. admira beaucoup cette montre unique et la fit compléter par un décor que nous exécutâmes à Paris, d'après les documents d'Etienne Delosne, le célèbre ornemaniste de la Renaissance.

Il manquait à cette montre diverses complications réellement intéressantes, telles que la grande sonnerie en passant et l'équation du temps; la grande sonnerie qui fait parler la montre à chaque quart d'heure, l'équation qui indique à tout moment de l'année la différence entre le temps moyen et l'heure du soleil. M. A.-A. de C. M. nous témoigna donc ses regrets de posséder un objet unique, il est vrai, mais encore très incomplet et nous soumit son dessein de faire exécuter une autre montre qui réunirait réellement tout ce que la science et la mécanique pourraient réaliser à ce jour sous un volume portatif.

Nous étudiâmes attentivement son programme. Il était tellement complexe qu'il nous fallut, a priori, écarter les complications de nature à nuire à celles que nous tenions absolument à y introduire. Les éclipses, les marées, la seconde foudroyante furent rejetées comme impraticables. Au contraire, nous donnâmes toute notre attention au mouvement sidéral que devait animer un joli ciel bleu parsemé d'étoiles, placé au centre de notre montre. Il y avait là, pensions-nous, une véritable nouveauté en horlogerie - et elles sont rares! - Que n'a-t-on pas fait depuis le XVIe siècle? Nous voulûmes aussi que le côté ciel fût décoratif. Il nous sembla qu'un cercle de 24 heures, représentant la révolution diurne de la terre autour du soleil se présentant devant chaque méridien terrestre une fois par 24 heures, donnerait à notre cadran un aspect intéressant et décoratif.

Leroy 01

Enfin, le plan général fut soumis à M. A.-A. de C. M. qui l'approuva, tout en nous exprimant ses regrets de voir éliminées certaines complications importantes. L'exécution de la montre ultra-compliquée (qui reçut plus tard le numéro hors série 01) fut décidée en janvier 1897. Nous devions appliquer les complications suivantes:

1° Le quantième de jours; 2° Le quantième de dates; 3° Le quantième perpétuel des mois et années bissextiles; 4° Le millésime pour cent ans; 5° Les phases et l'âge de la lune; 6° Les saisons, soltices, équinoxes; 7° L'équation du temps; 8° Le chronographe 9° Le compteur de minutes avec remise à zéro; 10° Le compteur d'heures 11 ° Le développement de ressort; 12° La grande sonnerie en passant, petite sonnerie, silence; 13° La répétition de l'heure, des quarts et des minutes, avec rouage silencieux sur 3 timbres faisant carillon; 14° L'état du ciel dans l'hémisphère boréal, au moment du jour indiqué par le quantième (le ciel étant animé du mouvement sidéral, c'est-à-dire avançant de 3 minutes 56 secondes par jour sur le temps moyen;Un ciel et un horizon pour Paris, avec 236 étoiles; Un ciel et un horizon pour Lisbonne, avec 560 étoiles; 15° L'état du ciel dans' l'hémisphère austral (au moyen d'un mécanisme de rechange animant le ciel d'un mouvement de rotation de l'ouest à l'est); Un ciel et un horizon pour Rio de Janeiro, 611 étoiles. 16° L'heure de 125 villes du monde; 17° L'heure des levers du soleil à Lisbonne; 18° L'heure des couchers du soleil à Lisbonne; 19° Un thermomètre métallique centigrade; 20° Un hygromètre à cheveu; 21° Un baromètre; 22° Un altimètre pour 5 000 mètres; 23° Un système de raquetterie permettant de rectifier le réglage sans ouvrir la montre; 24° Une boussole; 25° Sur la boîte, les douze signes du zodiaque.

C'est en tremblant que nous acceptâmes d'exécuter un programme aussi chargé; nous entreprenions une oeuvre bien téméraire. Pour la mener à bien, il nous fallait compter sur le concours moral et pécuniaire de notre client. Que de désillusions n'allions-nous pas avoir! Que d'à-coups, que de reculs n'allions-nous pas subir en abordant chacune de ces délicates complications! Nous avions raison de ne pas douter du concours si effectif et si réconfortant de M. A.-A. de C. M.; à aucun moment il ne nous fit défaut.

Au fur et à mesure de l'achèvement du travail, nous lui soumîmes nos réflexions et nous reçûmes toujours de lui des renseignements précis, énoncés en termes si clairs que rien ne pouvait échapper à l'attention. A l'Exposition universelle de 1900, nous pûmes soumettre au Jury International des Récompenses la montre la plus compliquée qui ait jamais été faite! Elle provoqua un étonnement général, tant par son mécanisme que par l'exactitude de ses fonctions et la perfection de la main-d'oeuvre. Nous pouvons dire, sans prétention exagérée, que cette oeuvre contribua dans une large mesure à la récompense qui nous fut décernée (Grand Prix).

Cependant notre merveille n'était pas achevée; elle était complète, voilà tout. Il fallait en finir toutes les parties, en assurer toutes les fonctions et, enfin, terminer la boîte au goût de son futur propriétaire. Cette partie du travail fut longue et pénible. Nous n'avions plus à compter sur nous seuls. Il fallait servir de trait d'union entre un artiste, M. L. Manini, chargé, par M. A.-A. de C. M., du dessin primitif et un autre artiste chargé de l'exécution, à Paris; chacun d'eux ayant de l'oeuvre une intuition très différente. Le travail de ciselure dans l'or, qui couvrait le boîtier, très étendu, aux reliefs très inégaux, variant entre 0,50 mm d'épaisseur dans les creux jusqu'à 3,50 mm à l'endroit des reliefs, fut enfin exécuté dans des conditions tout à fait satisfàisantes et qui font le plus grand honneur à notre artiste ciseleur, M. Burdin.

World Tempus

World Tempus

Etiquetas:

Art,

Lisbon Story,

Technotronic,

Time is of the essence

Subscrever:

Mensagens (Atom)