The Power of Reading

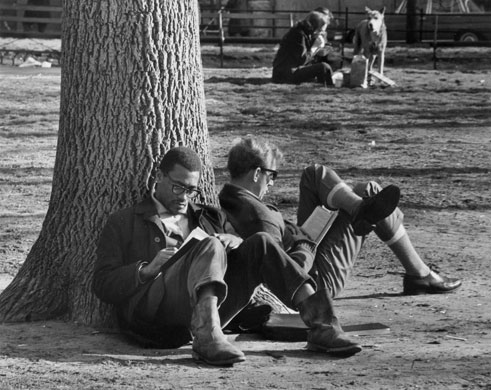

One of my favourite André Kertész photographs shows two young men sitting with their backs to a tree, each absorbed in a book. Both are wearing glasses; both use their thighs as a lectern; the one facing forwards is black, the other, in profile (a dead ringer for Woody Allen), is white. Their proximity suggests they know each other and are friends. And given the time and place of the composition, the photo could serve as an icon of the civil rights movement – racial harmony as observed in Washington Square, New York City, 1969. What's equally striking, though, is how separate the two men are, how oblivious to each other's presence (and to the camera). They might be friends but their real companions are their books.

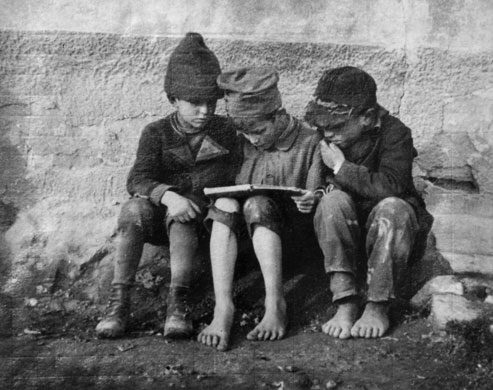

The Budapest-born Kertész enjoyed a long life (1894-1985), visited many countries and was involved in several different artistic movements. But wherever he went and whatever the commission, a constant preoccupation was with people reading. In one of his earliest and most moving images, three small boys (two of them barefoot) crouch over a book in a Hungarian street in 1915; in one of the last, a young woman stands reading in the shadow of a vast Henry Moore statue. Ferocious concentration is common to both. The act of reading involves no action, beyond turning the page. But the mental activity is intense, and it's this that fascinates Kertész.

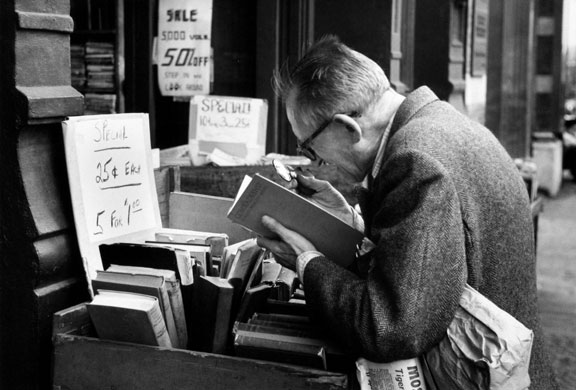

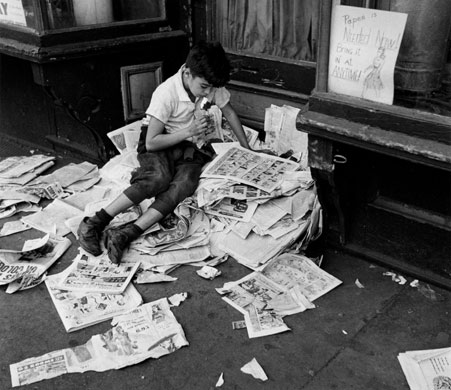

When paintings and sculptures depict a man or woman with a book, this usually signifies that they are studious, saintly, noble and wise – persons of substance. Kertész's approach is different. Apart from one semi-surrealist shot of Peggy Guggenheim, with an open book in the foreground, he has no interest in the great and good. The Bowery bum retrieving a newspaper from a wastebin; a woman kneeling over a text in a Manila market; gondoliers, circus performers and street vendors snatching time between work duties to peruse a book or magazine – Kertész's subjects are often people you wouldn't expect to see reading. What the camera captures is their thirst for knowledge or hunger to escape their circumstances. One memorable image features a boy sitting in a New York doorway in 1944, amid a heap of newspapers left there to alleviate the wartime shortage ("Paper is needed now! Bring it at any time," reads the poster behind him). Times are hard yet the boy looks perfectly happy: amid the detritus, he has found a page of comic strips.

Whereas books are traditionally thought of as an indoor pursuit, most of Kertész's subjects are caught reading outdoors. The venues aren't just parks and beaches. There's a whole sequence of images taken in Greenwich Village in the 1960s and 70s, showing people reading high above the street, on tenement rooftops, penthouse balconies, metal stair-ladders and window ledges. Enrapt as they are, the readers seem indifferent to the chimneys, ventilation pipes and washing lines that surround them: away from the crowds, each has found a space to be alone. The setting is tough and urban. Yet there's a spiritual quality, too – reading as a stairway to heaven.

Portrait painters evoke the spiritual intensity of reading by coming in tight on the face and body: the lowered eyes, the meditative brow, the hands piously folded under the spine of the text. The illustrations in Alberto Manguel's wonderful book A History of Reading include countless examples of this, not least the painting which serves as its cover, Gustav Adolph Hennig's Reading Girl. In Kertész's photos, by contrast, the perspectives are longer and the subjects unaware that they are subjects: he shoots from a distance, so that we see the surrounding environment rather than the title of the book that's being read. The lack of close-ups isn't an obstacle, since the faces of readers give nothing away: their only engagement is with the book. The light and shade emphasise the transcendental power of reading. Here are people on an inner journey, while physically remaining still.

Kertész didn't live to see the age of the internet or to hear the funeral rites for the age of print. But his photos of readers aren't just a historical document or an exercise in nostalgia. The essential image he works with is timeless: human interaction with the written word. The physical forms in which we receive the word may be changing. But even when ebooks and Blackberries have taken over, that central image will remain: a text held in the hand and a head bowed over it. Andre Kertész, On Reading, is at the Photographers' Gallery, 16-18 Ramillies St, London W1 until 4 October.

Comentários