The Translator as Shadow Novelist, by Maureen Freely

Outside the Anglophone world, it is not unusual for novelists and poets to work at some point in their lives as translators. Though most will say that they did so mainly to subsidise their own writing, it is often clear, when you look at that writing, that it has been enriched by the imaginary conversations they've had with the poets and novelists whose words they have translated.

If there is such a thing as world literature, it is because today's most interesting writers are also well‑travelled readers and a lot of what they read is in translation. An up-and-coming Colombian novelist might be inspired not just by Borges, Conrad and Faulkner, but by contemporary novelists from Asia, Africa and Europe; his literary response to their work will go on to influence what his contemporaries on the other side of the world write next. These complex patterns of cross-fertilisation would end overnight if it were not for literary translators and the publishers who support them. So you'd think people would thank us, wouldn't you?

Well, sometimes they do, but in the next breath they'll tell you what a terrible career move you've made. To a degree, they're right, because the pay is pretty appalling. Although some translators get a sliver of the royalties, most work for a flat fee. We who translate from non-western languages will often discover, if a book becomes a world phenomenon, that most other translations will be from our translation and not the original. But by and large, we receive no extra fee and it is only when those working from our translations send us frantic emails that we discover how far our words have travelled.

World literature is the big new thing in literature departments, so you'd think our good name would be assured here at least. Sadly, universities and their regulators tend to be suspicious about translations, possibly because they don't know what yardstick to measure them by. For the last Research Assessment Exercise, I was asked to explain in precise terms how my translations had contributed to world knowledge. For the next one, I shall also have to demonstrate their economic impact.

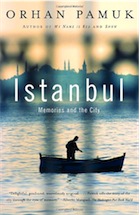

You could say that all we're doing, really, is replicating someone else's thoughts. And aren't we soon to be replaced by machines? I don't think so. Here is the sublime first sentence of Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul: Memories of a City as rendered by Google Translate: "A place in the streets of Istanbul, similar to ours in a different house, with everything I like, twin, or even exactly the same, starting from childhood lived another Orhan a corner of my mind I believed for many years." And here is the first sentence of his seminal novel, The Black Book, replicating the Turkish word and suffix order as closely as possible: "Bed-of top-from tip-to as-far-as stretched-out blue checked quilt-of rugged terrain-its, shadowy valleys-its and blue soft hills-its-with covered sweet and warm darkness-in Rüya face-down stretched-out sleeping-was."

When I translate, I become something akin to a shadow novelist. When I am shadowing Pamuk, what I want to do most is capture the music of his language as I hear it. Accuracy is important, but a lot of what I need to be accurate about lies deep below the surface. After consultation with the author, the first sentence of The Black Book became: "Rüya was lying face down on the bed, lost to the sweet, warm darkness beneath the billowing folds of the blue-checked quilt." The first sentence of Istanbulwas: "From a very young age, I suspected there was more to my world than I could see: somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours, there lived another Orhan so much like me that he could pass for my twin, even my double." I can see, even as I type these sentences, how ephemeral they are. Other translators will find their own ways to capture what they see and hear in the text.

I was initially drawn to this art because, after many years of journalism, I longed for a quiet life. I imagined weeks and months of solitary reflection in my favourite chair. And of course there were periods like this. But if you are translating a controversial author, the world is never far away.

My first rude awakening came while I was translating the first chapters of Pamuk's 2002 novel, Snow. A Turkish newspaper got in touch; having heard what I was up to, it wanted to know what I thought of the headscarf issue, about which Snow has a great deal to say. My innocuous answer (that a woman should be able to choose what she wears on her head) was transformed into a provocative headline ("I curse the fathers!"), following which I was bombarded with emails from an extremist Islamist newspaper. I could not help but notice that their questions were almost identical to those asked by an Islamist extremist in the chapter I'd just translated. It ends with said extremist pumping a few bullets into his interlocutor's head.

Over the years that followed, and especially during 2005 and 2006, when Orhan Pamuk and many other writer friends of mine were subjected to hate campaigns for speaking openly about the Armenian genocide, later to be prosecuted for insulting Turkishness, there were times when I felt as if I had wandered into the book I was translating.

There were also the lesser fictions in which I featured as a süperajan (no translation needed). Many Turks who feel ambivalent about Pamuk like to attribute his international success and most especially his Nobel prize to his translators, who have, they claim, "improved his words for western consumption". The ultranationalists who drove the hate campaign went so far as to say he had sold his country to Europe for the sake of his career.

If I were just a translator, I might not have thought it necessary to write in Orhan's defence in the media here and elsewhere. I might not have become involved in the campaigns for free expression that went on to change my life and will doubtless carry on doing so. But this seems to be the rule for translators and not the exception.

Most of us do a great deal off the page. More often than not, we are the ones who bring new authors to the attention of publishers. Some run programmes that bring together young writers from countries that were once at war. Some run programmes in schools, working with children who speak a language other than English at home. Many are also novelists, poets, journalists and teachers. Some – most commonly those who translate out of minority languages – are agents.

I know all this because there aren't very many of us. We all work for the dozen or so publishers which remain committed to fiction in translation even as the walls of fortress English grow and grow. If the art of literary translation continues to thrive in this country, it will be thanks to them, and also to the British Centre for Literary Translation, which is training the new generation, and the Translators Association, which speaks up for us when we're exploited, and the Independent foreign fiction prize, whose organisers work hard to take our best efforts to a larger audience.

Why do any of us bother, when the odds are so against us? Because it's fun to discover new books and new writers. It's gratifying to see at least some of them do well. For me, it makes a welcome change from my old life, when I mainly looked after number one, wasting acres of times fretting about bylines and book sales and column inches. Somehow, this feels more romantic and far more worthwhile.

Comentários