Gonzo

Alex Gibney is one of the most important documentarists at work today. Two of his recent films - Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, about high-level corporate corruption in America, and Taxi to the Dark Side, an account of US military interrogation and torture in Afghanistan and Iraq - are essential viewing for anyone seeking an understanding of our times. His films are sober, carefully crafted and thoroughly researched, politically committed but not propagandistic, and deeply felt without focusing the camera on his own bleeding heart.

He is thus considerably different from the subject of his latest film, Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr Hunter S. Thompson, one of the creators and most extreme exponent of the "New Journalism" of the 1960s, and the man who gave us that overworked phrase "fear and loathing". Thompson, who had an obsession with guns, owning 22 of them (all kept fully loaded), committed suicide with a gunshot to his head in 2005 at the age of 67.

The film is an impressionistic portrait of Thompson as eccentric libertarian, admired outsider, rebel, scabrous social critic. A romantic utopian, he was searching for the American Dream and lamenting its death. As an ambitious writer, he was chasing after that chimera "the Great American novel", but inevitably finding it eluded him.

Early on, Gibney takes us to the study in the Colorado farmhouse where Thompson lived for the last 40 years of his life, the camera scanning photographs of Mark Twain, William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway, the heroes he sought to emulate.

Thompson was one of three brothers raised in a lower-middle-class family in Louisville, Kentucky, and was in constant trouble at school and then in the US Air Force. The film, however, passes rapidly over the youth and early career, eager to get to the wild, rebellious 1960s, which he observed, participated in, helped shape the image of, and of which he was ultimately a victim through his reckless addiction to every possible kind of drug.

There is an extended section on his first book, Hell's Angels (1966), an excellent piece of reportage on California's motorcycle gangs, written after spending a year with them, and ending when he was given a terrible beating after they'd demanded a share of any money he made out of them. Gibney shows Thompson going to the self-destructive edge in writing this book and then plunging over that edge into Gonzo journalism.

Hell's Angels was participatory journalism that put the writer into the story and drew on the techniques of fiction. Gonzo happily stirred actual fiction into the brew (some of it extremely mischievous, as when he wrote of politician Ed Muskie as a drug addict) and added touches of the surreal. Thompson was introduced to the term 'Gonzo' by his friend, the Boston journalist Bill Cardoso; it's apparently an Irish-American term for the last man standing after an all-night drinking session. From 1970, British cartoonist Ralph Steadman illustrated many of Thompson's books and articles, and his bold graphic style, an expressionistic combination of George Grosz and Thomas Rowlandson, became an essential element in the Gonzo package. Steadman speaks with a warm, wry candour about their collaboration.

Having started out as a sport journalist, Thompson became immersed in politics. He ran unsuccessfully for sheriff in Aspen, Colorado, on an independent hippy ticket. More importantly, he covered all the presidential elections from 1968 onwards. "The Kennedys - they were his guys," one witness observes, but he became a friend of George McGovern, Gary Hart and Jimmy Carter, all of whom speak well of him, as does a less likely friend, the right-wing ideologue Pat Buchanan, who must have loathed everything Thompson stood for, yet arranged for him to ride in the back of Nixon's limousine during the 1972 election.

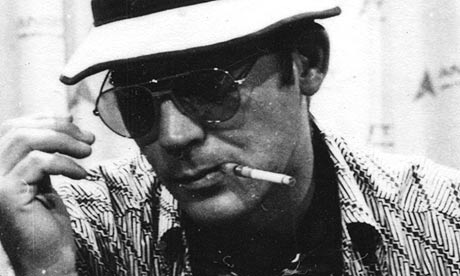

During this period, we see Thompson developing a public persona through his signature dark glasses, cigarette holder, floppy hat and outrageous behaviour and being taken over by it. By 1976, when travelling with Jimmy Carter, it was Thompson's autograph people sought, not the presidential candidate's. The peak of Thompson's madness was reached in 1974 when he accepted a Rolling Stone assignment to cover the Foreman-Ali 'Rumble in the Jungle' in Kinshasa. Instead of attending the fight (as more responsible New Journalists such as Tom Wolfe, George Plimpton and Norman Mailer did), he took a load of drugs and floated in his hotel pool wearing a Nixon mask and clutching a bottle of whisky.

Gibney's elaborately textured film draws on much home movie footage, new interviews, old TV appearances and clips from the feature films inspired by Thompson's antics (he's played by Bill Murray in Where the Buffalo Roam and Johnny Depp in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas). It's often hilarious and captures the spirit of the time, both in its early hopes and its inevitable disillusionment. Yet it's a sad movie and somehow inadequate in its lack of true pity or understanding. Thompson's first wife, Sondi, mother of his son Juan, put up with him for 20 years, until his excesses and egotism forced her to leave, and it is she alone who says: "I think his story was tragic."

And it is she who demurs from a general agreement that his suicide, like that of Hemingway, was somehow a courageous act. In this documentary, we watch a man go insane and destroy himself, his final act of madness being the funeral he organised in which his ashes were sent into the skies with red, white and blue fireworks from a self-aggrandising tower he'd designed with the help of Steadman.

Comentários