What Happens If No One Reads

By Spencer Klavan.for The Free Press.

No one reads anymore. This is something that teachers of literature like me are always saying. “Every generation, at some point, discovers that students cannot read as well as they would like or as well as professors expect,” wrote the scholar of literacy Martha Maxwell in 1979. But more and more, educators are finding that the last few years have been meaningfully different. Students are showing up at even high-end schools having never read a novel cover to cover. Columbia literature professor Nicholas Dames told The Atlantic’s Rose Horowitch that his students “struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot.” Last month, as students returned to school, a new study made headlines because it found that the number of Americans who read for pleasure has dropped an astonishing 40 percent since the start of the century.

As a college teacher, I’ve noticed this trend too. My students are perfectly earnest, interested in the world, and even willing to take it on faith when I tell them it’s important to do the assigned reading. They’ve heard throughout their lives that reading is an important component of their future success. But many of them have never gotten much personal enjoyment out of it or seen for themselves what a book can give them that a Wikipedia entry can’t deliver more quickly. Covid school closures probably accelerated the problem. AI chatbots threw it into hyperdrive by offering on-demand, made-to-order, correct-enough summaries of (and essays about) any book you can google. But all ChatGPT really did was intensify our growing need to ask the question: Why read? What is it about sitting with a book, a quintessential experience of civilized life until very recently, that can’t be automated or replaced?

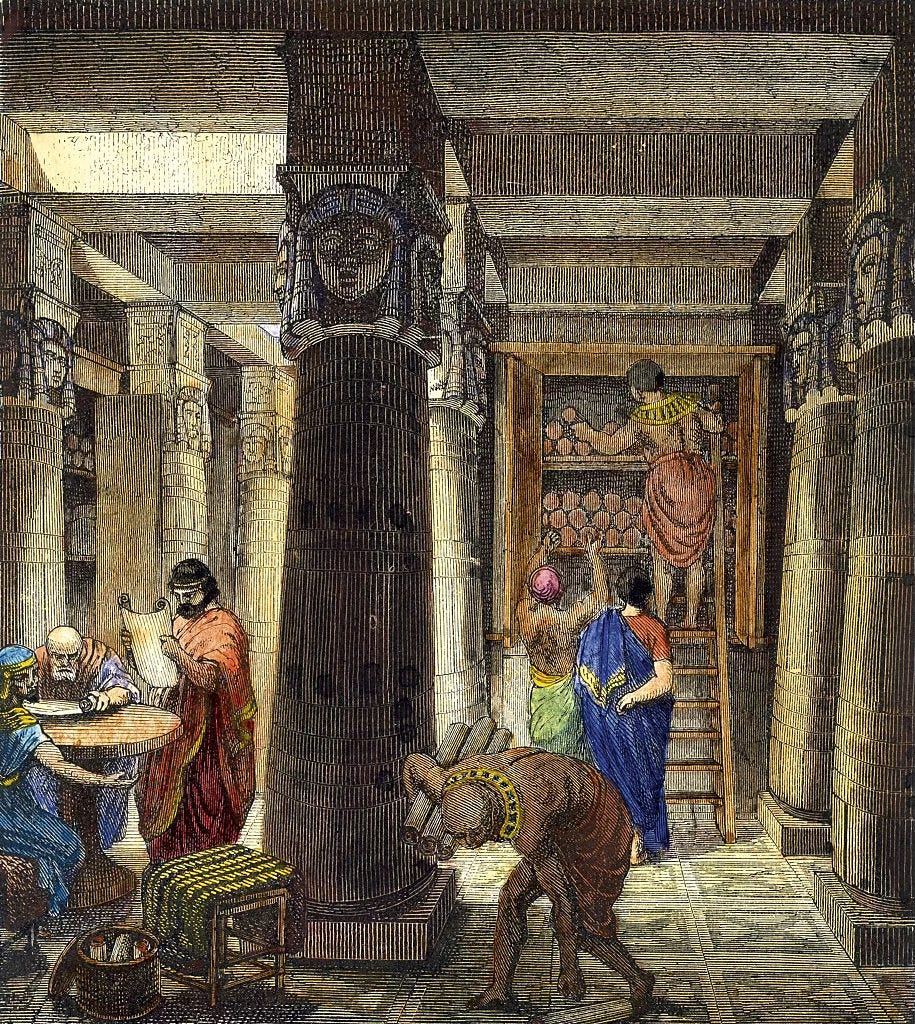

You can almost picture the Library of Alexandria as the ancient version of a cloud server bank somewhere out by Palo Alto, housing the sum total of recorded knowledge so that humanity doesn’t have to trouble itself with remembering.

The obvious irony is that Plato made this complaint in writing. The literary form he pioneered—the philosophical dialogue—is a way of using text for a different purpose than simple information storage. Dialogues were Plato’s way of recreating, in written form, the experience of conversation and intellectual exchange. You get into a relationship with the book and its characters. The experience—of reading it, of puzzling over it, of returning to it after a day or a year or a lifetime of reflection—becomes the point.

What Grok could never have done is prompt the recollection that arose in me from having spent a lifetime with books like Middlemarch—my inkling that this thought I was having was one I shared with a brilliant woman, long dead.

When Plato was a young man, the comic playwright Aristophanes produced his Frogs, in which the god Dionysus mentions offhand that he once passed the time when he was supposed to be on naval duty reading the text of another play, Euripides’s Andromeda. This is probably one of our earliest depictions in Western literature of someone reading alone for pleasure, imagining the characters striving and suffering and speaking in the mind’s eye. It’s a different thing entirely from using books as data dumps.

This other kind of reading—as a means of human connection rather than an information delivery system—has always struck some people as frivolous. Even in the 19th-century heyday of the European novel, fiction was often dismissed as a mere pastime, more reminiscent of Dionysus slacking off on his ship than of budding rhetoricians training in the art of statecraft. There’s a scene in George Eliot’s Middlemarch where Fred Vincy, dreamy brother of the rather shallow Rosamond, sits reading while his mother chatters about his “studies.” “Fred’s studies are not very deep,” interjects Rosamond, “he is only reading a novel.”

Of course, by dropping that line into her own novel, Eliot is giving her readers the exact same sort of wink Plato gave us in the Phaedrus. In some ways, the novel was the modern inheritor of the philosophical dialogue: the kind of writing whose whole point was getting to spend time with the characters, the kind that insisted on being lived and imagined rather than mined for facts or life advice. People who read truly great literature for its own sake, wrote C.S. Lewis, find that “their whole consciousness is changed. They have become what they were not before.”

And this may be the only kind of reading whose worth is not currently being replaced by machines. The self-help life hacks can be summarized, short-circuited, and then dispensed with. A novel cannot.

When I set out to write the paragraphs above, I woke up with that nagging sense of recollection that every lifelong reader knows. Somewhere—was it Middlemarch? David Copperfield?—there was a scene where a character says something like “she’s (or he’s) only reading a novel.” But I couldn’t quite place it. So I asked Grok. A perfect use case: It confirmed my hunch and led me back to Middlemarch, where I found the quote. That’s the kind of value AI can provide. It can outdo almost any other current tool for streamlining whatever fact-gathering task you would once have had to accomplish with a card catalog, or an encyclopedia, or a search engine.

What Grok could never have done, though, is prompt the recollection that arose in me from having spent a lifetime with books like Middlemarch—my inkling that this thought I was having was one I shared with a brilliant woman, long dead. Above all, Grok could never have given me what Eliot does in the moment right after Fred’s sister carps at him about his reading habits: “Fred drew his mother’s hand down to his lips, but said nothing.” That utterly real gesture of silent acceptance, his irritation conquered by the domestic mercies of ordinary love—that’s the kind of thing novels offer that summaries can’t.

This is what I tell my students when I try to explain to them why they can’t outsource their memories or their homework to a souped-up predictive text program. They will be constantly nudged and tempted to do so—OpenAI already offers students various discounts and free promos for its premium service, clearly hoping to encourage the habit of relying on ChatGPT for all manner of things. It will be up to the new generation to decide which tasks they want to delegate to the machines. But if they choose reading, they will have cheated themselves terribly. The art of really taking in literature is one of the great liberal arts—it’s an act of pure freedom, something you do for no other reason than to do it.

It may be a dying art. There is now a whole genre of social media posts about how to extract the value from books without reading them. “Reading books is now a waste of time,” wrote Davie Fogarty, whose bio on X credits him with “$850m in Shopify ecommerce sales.” Books are obsolete, thinks Fogarty, because “AI reasoning models can distill key insights and tell you exactly how to implement them based on everything they know about you.” And he’s perfectly right about that first kind of reading—the kind that self-help writing and business strategy manuals require, the kind that treats books merely as convenient packaging for “action items” which could just as well be slides on a PowerPoint deck. There has always been a cottage industry of digests and summaries, SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, to abridge that kind of reading. Now there are apps like Blinkist, which do the same thing using AI.

It will be up to the new generation to decide which tasks they want to delegate to the machines. But if they choose reading, they will have cheated themselves terribly.

But the other kind of reading, the kind that consists in watching George bring his mother’s hand silently to his lips, can’t be summarized. What would be the point? If ChatGPT could tell you what a meal tastes like, would you not feel the need to eat it?

It’s easy (and fun) to imagine what sorts of “key insights” a chatbot might extract from the classics for the benefit of a Shopify mogul. “The Iliad: Leverage your assets at work.” “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: Underpromise, overdeliver.” I asked Grok about The Brothers Karamazov and it told me, “We’re all a mess of contradictions.” And so we are. Why didn’t Dostoyevsky just say that?

Here is why. Relatively early in the novel, the protagonist Alyosha hears a story in which a nasty old hag dies and wakes up in hell. Her guardian angel pleads before God on her behalf, and recounts the one good deed she ever did in her life: She gave an onion to a hungry beggar. The angel takes that onion and holds it out to the wretched sinner, telling her to grab on to it so that she can be pulled up to heaven. And just like that, every soul in the lake of fire clutches at her heels and starts getting carried up along with her. “But she was a very wicked woman and she began kicking them. ‘I’m to be pulled out, not you. It’s my onion, not yours.’ As soon as she said that, the onion broke.”

Probably whoever cares to feed this story into ChatGPT can find a pat little moral in it: Don’t be selfish, think of others, feed the poor. But in the next chapter Alyosha dreams of his mentor, the saintly Father Zosima, whom he misses desperately, rejoicing at the wedding feast in heaven and saying: “I gave an onion to a beggar, so I, too, am here. And many here have given only an onion each—only one little onion . . . What are all our deeds?” And how can I summarize the meaning of that passage except to say that when first I read it I laid the novel aside and wept, feeling suddenly that I, too, might be saved?

As I tell my students, no one can force you to do that kind of reading. If we are transitioning away from the Gutenberg age of mass literacy, out of the world of Dostoyevsky and Eliot into one where books once again become the preoccupation of a select few, I can’t stop that from happening. But we will be the poorer for it, our lives a little more flattened and emptied. After all, what in the end will all this efficiency and optimization have been for? If we cease to see the point of reading, what are we going to do with all that time freed up by our devices?

“What are you trying / to be free of?” asks the poet Joseph Fasano in a poem addressed to a “Student Who Used AI to Write a Paper.” Is it “the living? The miraculous / task of it?” But “love is for the ones who love the work.” The kind of reading that retains its worth in the age of AI is the kind that has no measurable ROI, no scalable metrics, no immediate market value of any kind. It is like life in that the point of it is the story itself, and the only way to “get” it is to dwell in it and let it change you.

It has nothing to offer, in other words, besides the communion of soul with soul. But if we can’t value that, what is anything else worth?

Comentários