The Japanese landscapes that inspired Studio Ghibli films

by Mizuki Uchiyama for BBC Travel.

As Studio Ghibli turns 40, we visit the forests, springs and villages that inspired its most beloved films, and meet those preserving their magic.

From moss-draped cedar forests to steamy bathhouses and suburban woodlands, the animated worlds of Studio Ghibli often feel fantastical yet familiar. Across 23 feature films, the Japanese studio's vividly drawn landscapes – where kurosuke (soot sprites) scuttle and giant cat-buses roam – have transported generations of viewers into realms where nature and fantasy blur.

But many of these beloved settings weren't born from pure imagination. They were inspired by real places across Japan – some sacred, others endangered but all profoundly cherished.

As Studio Ghibli celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, we're exploring the real-world places behind some of its most iconic films.

Yakushima: The sacred forests of Princess Mononoke

In the opening scenes of the 1997 masterpiece Princess Mononoke, a boar charges through a misty, primeval forest filled with towering trees and ancient spirits. This world is widely believed to be based on Yakushima, a Unesco-listed island off southern Kyushu that's revered for its spiritual significance.

In Yakushima, 1,000-year-old cedars rise from carpets of moss, and rainfall nourishes a dense, dreamlike forest said to house kodama (tree spirits). "Every direction – up, down, front and back – was completely enveloped in green," recalls Yumi Takahashi, a Tokyo-based office worker who recently visited the island. "It felt like being deep underwater, surrounded by forest instead of water. It was mystical."

Taro Watanabe, the head of Guide Office Sangaku Taro, which leads mountain excursions on the island, says the Studio Ghibli connection still draws visitors from around the world. "Even now, many people come to Yakushima because of Princess Mononoke," he explains. "But in recent years, tourism has actually quietened down. I hope more people will come and experience the island's nature for themselves."

Yakushima's forests are considered ecologically unique: its varied subtropical coastlines and alpine peaks boast endemic plant species found nowhere else in the world. But these fragile habitats face mounting threats from overgrazing deer and climate change, which is raising temperatures and triggering disruptive landslides. Conservationists and local guides are working alongside Unesco and government agencies to limit visitor impact, protect old-growth cedars and restore damaged forest areas to ensure Yakushima's enchanted landscapes endure long after the credits roll.

Dōgo Onsen: The bathhouse of Spirited Away

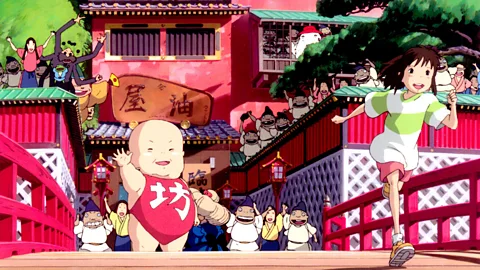

A red bridge leads to a towering bathhouse, its windows glowing gold against the night. This is the domain of Yubaba, the greedy witch who runs the bathhouse in the Oscar-winning Spirited Away, a film forever linked to the Dōgo Onsen Honkan hot springs in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture.

Dōgo Onsen's history stretches back roughly 3,000 years, making it one of the oldest of Japan's nearly 3,000 onsen (hot springs). With its winding corridors, creaking floors and tiled rooftops stacked like a pagoda, the building captivated Studio Ghibli's co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. While he never confirmed the inspiration outright, the word "Dōgo" appears in his storyboards and its watchtower and rooms are unmistakably echoed in the film's Aburaya bathhouse.

"Guests often say, 'This is the bathhouse from Spirited Away, isn't it?'" says Kazuya Watanabe, public relations officer at the Dōgo Onsen Consortium. "We hear that kind of conversation a lot."

Today, Dōgo Onsen welcomes both bathers and Ghibli fans. After a major restoration project finished in 2024, the bathhouse is once again open to the public and recognised as an Important Cultural Property of Japan. "We want to pass this place on to the next generation," Watanabe says. "It's a treasure of Matsuyama, and we hope it will remain so for years to come."

Sayama Hills: The forest of Totoro

Of all Studio Ghibli's fantastical creations, perhaps none is more iconic than Totoro – a round, benevolent forest spirit with the body of a beanbag. He lives among camphor trees and rice fields in My Neighbor Totoro. That setting, too, was drawn from real life.

The Sayama Hills form a 3,500-hectare swath of satoyama (a mosaic of woods, farmland, rice paddies and wetlands) that stretches across the borders of Tokyo and Saitama prefectures. Miyazaki lives nearby, and Studio Ghibli has acknowledged that these hills were among the landscapes that inspired the film.

Most of the areas known today as "Totoro's Forest" are protected by the Totoro no Furusato Foundation (established in 1990 with support from Miyazaki) and located in the northern portion of Sayama Hills. Some are tucked beside private homes or along narrow streams, others spread around the shores of Lake Sayama, but all represent a traditional rural landscape that once framed everyday life across Japan. The winding paths here often feel like the very lanes where Mei wanders in My Neighbor Totoro. From the ridgelines, visitors catch sudden glimpses of Lake Sayama, a vast reservoir whose still waters reflect Mount Fuji on clear days.

Kurosuke's House, a 120-year-old farmhouse, resembles the old, empty countryside structure where the family finds refuge in My Neighbor Totoro. The wooden building retains the charm of old Japan, with tatami-mat rooms, sliding fusuma doors and shoji screens. Inside are playful recreations of soot sprites – the tiny dust-like spirits that scurry through the shadows in the film. The grounds also feature old tea-drying sheds and hand-pumped wells, adding to the sense of stepping into the past.

Since its founding, the Totoro no Furusato Foundation has acquired more than 50 parcels of woodland to prevent suburban development. Volunteers and travellers can help with undergrowth clearing, tree pruning and trail repairs, while staff at Kurosuke's House run workshops and guided walks here they explain their conservation work and why these woods are worth saving."Visitors are often surprised to learn not just about the forest, but about the grassroots efforts that sustain it," says Mie Hanazawa of the Totoro no Furusato Foundation.

Comentários